Hamstring injuries are the kryptonite of many a field sport athlete. But why do hamstring strains happen? And more importantly, how can we reduce the likelihood of them happening?

In this blog you will learn:

-

Why you need long and strong hamstrings (and how to get them)

-

Why hamstring injuries can be the fault of inadequate strength, coordination or improper sprinting technique

-

Why sprinting 1-2 x a week at maximal speed may be the most effective hamstring \’prehab\’ strategy

All muscular injuries occur because the stress placed on the body exceeds the body\’s ability to tolerate said stress. In terms of stress to the hamstring musculature the following factors can increase the stress the hamstring group has to deal with:

#block-83a15b21a4585abf5475 {

}

-

Inadequate muscular capacity (Freckleton 2014)

-

Inadequate mobility

-

Improper firing patterns

-

Inadequate strength at end range

-

Harsh braking patterns in sprinting (e.g. heel striking)

As with everything in S&C there is a law of diminishing returns. Having the mobility to do the splits 3 different ways will not act as a cure all against hamstring tears, the same way that a double bodyweight deadlift is a starting point where strength level is concerned, not the holy grail of hamstring injury prevention. That said, here are some measures that are favourable for reducing hamstring tears:

-

20 hamstring bridges (Freckleton 2014)

-

Increased eccentric hamstring strength (working towards a full range nordic, and a double bodyweight RDL are good examples of this)

-

The ability to at least get the foot past the knee of the down leg in an active straight leg raise (a 2/3 score in the FMS).

Another critical aspect to mention is the mechanism of injury. Although the biceps femoris muscle of the hamstring group often gets injured during high speed running, the semitendinosus is typically injured via an overstretch mechanism (Aksling 2012).

This means the hamstring musculature not only needs to be strong enough to cope with end ranges of motion, but that athletes needs to be conditioned and coordinated enough to deal with the demands of high speed running.

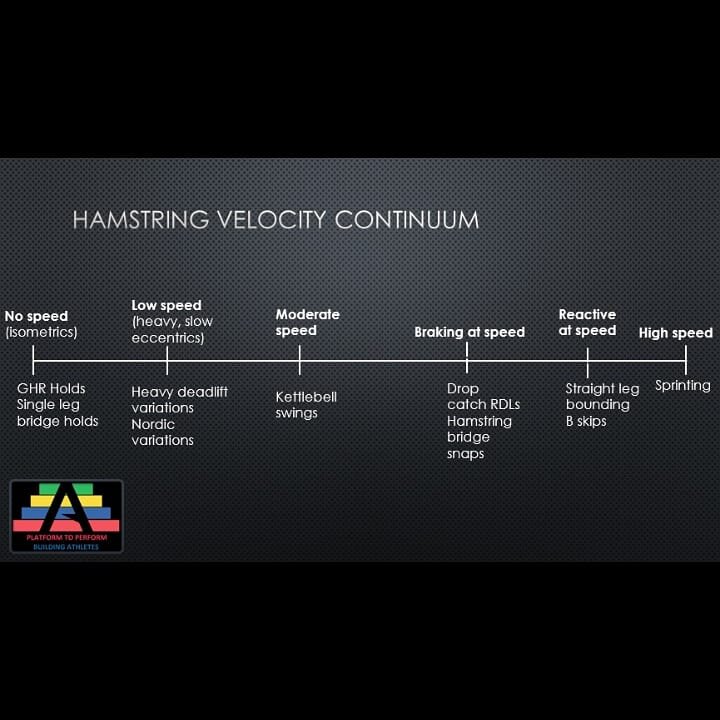

Whilst we need the hamstrings to be strong, and long (Presland et al 2018) we also need to condition them under high speeds. This is yet another reason why a double bodyweight deadlift is a starting point…not an ending point, when it comes to hamstring protection. The key question should not be, how strong can we get, but rather how many different ways can we express this strength. For example, can we express strength:

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1579096064637_6388 {

}

-

At high speeds (e.g. sprinting) and low speeds (under heavy load, like a deadlift variation)

-

Eccentrically (in a movement’s down phase, e.g. nordics), isometrically (holding positions statically) and concentrically (in a movement’s up phase, such as a trap bar deadlift)

-

In knee dominant (e.g. Nordic variations and hamstring slider work) and hip dominant movements (RDLs, glute ham raise)

-

In double leg (deadlift variations) and a single leg patterns (single leg deadlifts)

-

Within shallow ranges of motion, mid-range of motion end ranges of motion (such as a full Nordic, or razor curl, or RDL)

On a final note, hamstring injuries that occur during high speed running are also due to athletes being in the wrong positions, and/or with the wrong timing when it comes to sprinting. Low hurdle run throughs, like RDLs and Nordics, are not a cure all for fixing improper sprinting technique, but are certainly a good starting point.

Although hamstring injuries occur during high speed running, failing to expose athletes to top end speed work will inevitably see them being sent out onto the field of play having not been sufficiently prepared for the demands of the game; by performing top end speed work 1-2 x a week (e.g. 4 x 40m of sprinting with 2-4 minutes recovery) you will be providing a sufficient enough dose of high speed hamstring conditioning to help improve the muscles tolerance to a situation where it is most vulnerable.

Key Take Homes:

In order to reduce the risk of hamstring injuries:

-

Perform top end speed work 1-2 x a week

-

Hamstrings need to be long and strong, train progressively towards end ranges of motion

-

Use hip dominant (e.g. RDLs) and knee dominant (e.g. Nordics, or hamstring sliders) exercises, in bilateral and single legged patterns

All tests mentioned in this article can be found below

References & Resources

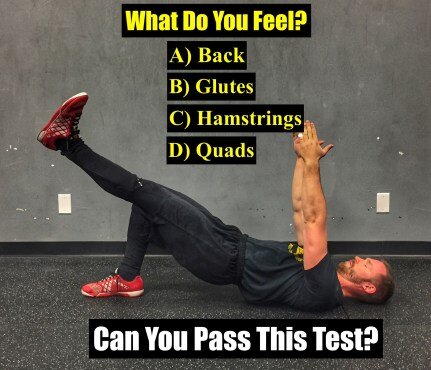

The single leg bridge test for assessing hip extension

Single leg hamstring bridge test

Active straight leg raise test

Askling, C.M., Malliaropoulos, N. and Karlsson, J., 2012. High-speed running type or stretching-type of hamstring injuries makes a difference to treatment and prognosis.

Presland, J.D., Timmins, R.G., Bourne, M.N., Williams, M.D. and Opar, D.A., 2018. The effect of Nordic hamstring exercise training volume on biceps femoris long head architectural adaptation. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 28(7), pp.1775-1783.

Oakley, A.J., Jennings, J. and Bishop, C.J., 2018. Holistic hamstring health: not just the Nordic hamstring exercise.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1579096064637_9134 {

}