Plyometrics are the social media of the modern world.

You may have heard of plyometrics… But you might be confused or unaware of their actual purpose.

By the end of this blog you will know:

· The benefits of plyometric training for the youth athlete

· Some key guidelines for how to perform them

· How to classify plyometric intensity

· How to program plyometric training for the youth athlete

#block-4e12ce27801a31680b41 {

}

Plyometric training improves an athlete’s rate of force development.

Whilst strength training improves how much force an athlete can produce, plyometric training can help athlete’s produce this force more quickly.

This is important because a large number of actions in sport occur within fractions of a second, and plyometric exercises give athlete’s the opportunity to express force at more sport-specific speeds.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_5545 {

}

Whilst phrases like ‘you need to train fast to be fast’ sound like they make intuitive sense, the reality is no one cares how quickly an athlete produces force if they don’t produce very much of it.

Think of a boxer with lightning fast hand speed whose rapid punches do little to discourage an aggressive opponent…this is because although they produce force quickly, there is not that much of it in their punches.

So what about endurance sports that don’t necessarily rely as heavily on explosive efforts?

Well not only have plyometric exercises been shown to improve athlete’s ability to produce more force in less time, a key determinant of success in elite sprinting (Morin et al 2015), but sufficient exposure to appropriate plyometric exercises has also shown to improve efficiency in well-trained distance runners (Turner et al 2003), punching power in boxers, and performance of block starts in adolescent swimmers (Bishop et al 2009).

If you’re reading up to this point you may be wondering what a plyometric exercise is, or are curious as to what actually makes an exercise a ‘plyometric’ in the first place?

Firstly, it is important to differentiate between jumping, hopping and leaping and what I would refer to as a ‘true’ plyometric.

This difference is more than just semantic. The reason why it is important is because each of these activities carries a different level of training stress.

Athlete’s get injured because the stress that is applied to them exceeds their ability to tolerate it.

I use the word stress rather than training because when working with school kids, injuries are far more common around exam period independent of changes in physical training loads (Milewski et al 2014)

Jumps are defined by a double leg takeoff or landing with a horizontal or vertical emphasis.

Hops are defined by the takeoff and landing occurring on the same leg. These can have a horizontal or vertical focus.

Leaps are defined by the takeoff and landing occurring on different legs.

Jumps, hops and leads can all become plyometric exercises if an element of ground time is introduced. By ground contact time, I simply mean the time it takes for an athlete to make contact with the ground and rebound off of it.

Rebounding exercises (i.e. true plyometrics) tend to more stressful than singular jumps, hops or leaps.

I use the phrase ‘tend to be’ not to sit on the fence, but because determining the intensity (i.e. the training stress) can be determined by answering 4 questions from Mike Young’s presentation at the 2017 Child to Champion conference

· Did the athlete fall a great distance? (you will fall further by performing a tuck jump jump vs a box jump)

· How fast was the athlete moving? (you will be moving faster in repeated tuck jumps than slow skipping)

· How springy was the athlete? (Did they rebound off the floor more like a beach ball or a bouncy ball? Elite high, long, and triple jumpers will not fold like a deck of cards during intense rebounding activities, you or I however…)

· How was the load distributed (single leg, such as hop, bound or leap, double leg such as jump, or asymmetrical such as a staggered stance jump)?

You may be thinking… Great, but where the hell do I start with the million and one plyometric variations?

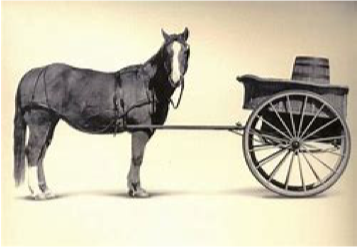

When it comes to plyometric training, think of it like stepping into your car… You would want to check the brakes work before putting your foot on the gas.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_17759 {

}

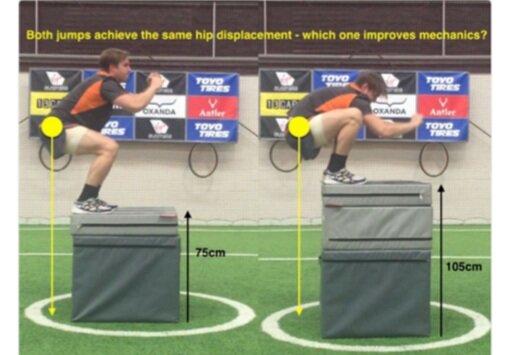

The starting point for plyometric training for the youth athlete has to be landing mechanics. All too often I see people obsessing about how far or high a kid can jump before seeing that they can do it correctly and safely.

Again going back to the car analogy, if you took your car in for an MOT and all they did was check the brakes and the accelerator…you would wonder whether they had a thorough enough job.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_25994 {

}

The plyometric equivalent to this dangerous shortcut would be to go straight from assessing landing mechanics to something like box jumps. Box jumps in themselves aren’t a bad exercise, but the below picture illustrates how the desired outcome and the actual performance of them often don’t marry up as they should.

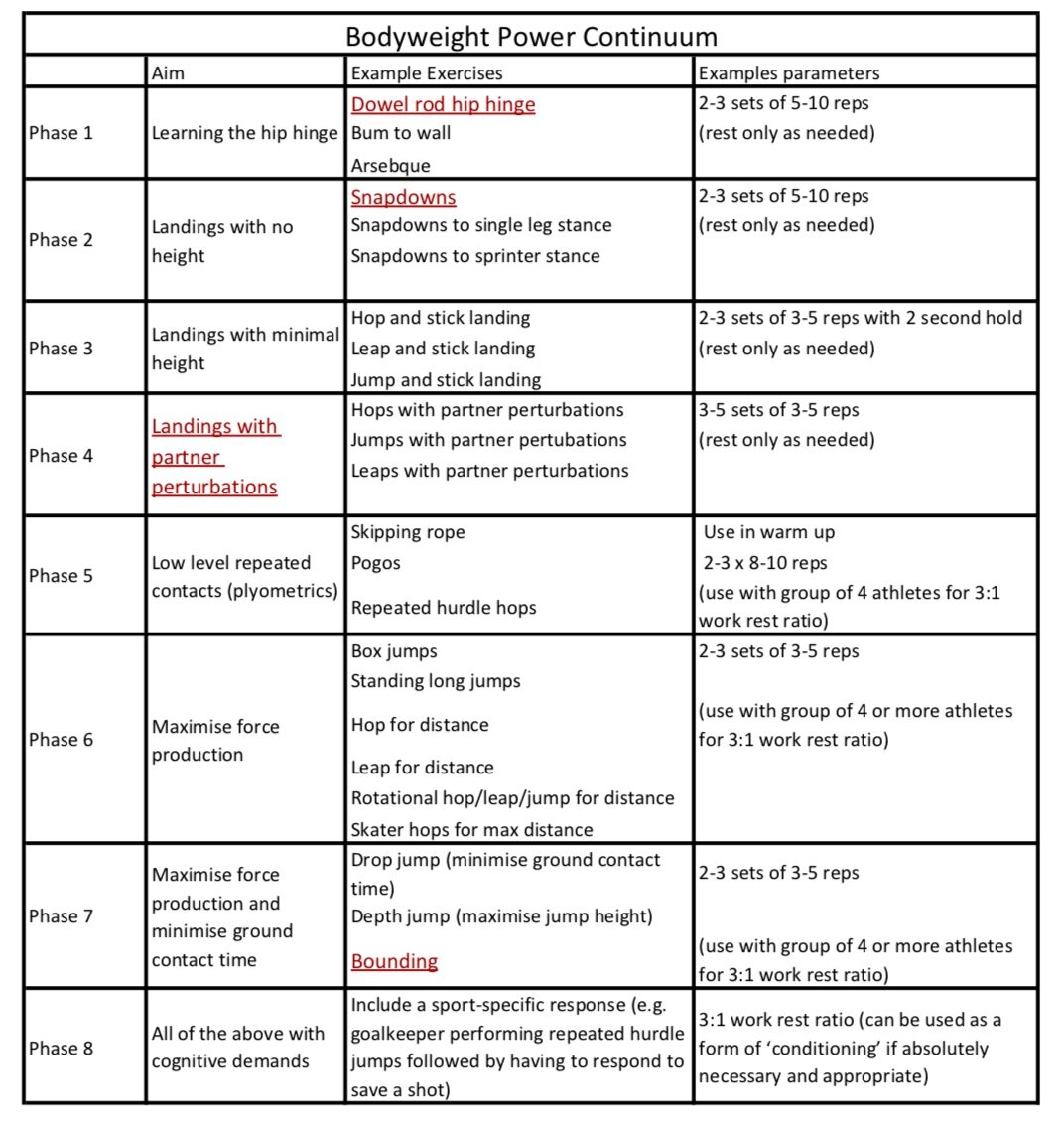

Since we know jumping and plyometrics are not necessarily the same thing, for the sake of consistency, you can see example progressions in my Bodyweight Power Template below.

It is worth noting that whilst I do not see each phase as mutually exclusive, it does help to have a rough guideline in place of which types of exercises are most appropriate at which stage of an athlete’s career.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_32990 {

}

That said, you may well think that you need to improve your young football team’s ability to jump high so they can win more headers… But you are placing the cart before the horse if you are emphasising jump height before landing mechanics.

In my continuum something like box jumps would not be introduced until the athletes can demonstrate they can land well when moving vertically, laterally, rotationally, off both legs and with perturbations (a partner nudging in to you makes for great fun with youth athletes, but also helps add protect against ankle sprains and re-coordinating the body when inevitable collisions occur).

Whilst there is certainly nothing wrong with seeing where your young athlete or child is at, the exercise itself does not guarantee an adaptation, it is the way it is performed, how they are exposed to said exercise (i.e. sets, reps, rest between, frequency etc).

With this in mind you may be thinking: ‘So I have a rough understanding of how to judge easier vs harder variations… What does this look like for my child’s training?’

Any exercise designed to improve rate of force production should be done with the attempt to move the body as fast as possible, meaning the rest period between sets should enable you to at least maintain force output.

Highly experienced jumpers will need much more rest than 10 year old performing hop-skotch… But if the jump height, distance or speed of the floor slows, you may want to consider giving your athletes more rest or lowering the reps.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_46301 {

}

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_67939 {

}

Finally, you may be wondering how long should an athlete be kept in a given phase before moving on?

Whilst it is easy to fall into the trap of progressing an athlete simply based on competency, I have yet to see any literature post about adaptations occurring in anything less than 5 weeks (Blazevich et al 2003).

As a starting point, 5 weeks of 1-2 x week of plyometric exposure might be an effective time frame, with athletes being able to demonstrate the global aim of the phase across variations in all 3 planes of motion, on both legs and potentially even doing so with a friendly nudge from their team mates.

Key Take Homes

· Although not the same thing, jumping and plyometric activities can be placed into 3 broad categories: plyometric stabilisation, plyometric strength and plyometric power.

· The ‘stress’ of a plyometric activity can be estimated using 4 questions (Did the athlete fall a great distance? How fast was the athlete moving? How stiff/springy was the athlete on ground contact? How was the load distributed?

· Check the brakes work before you work the accelerator (learn to land properly before you work on jumping and/or rebounding exercises)

Key Resources

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5gs8ePEvDLY&t=574s Plyometric Implementations to Decrease the Likelihood of Injury

NASM Essentials of Sports Performance Training Chapter 8-Plyometric Training Concepts for Performance Enhancement

References

Bishop, D. C., Smith, R. J., Smith, M. F., & Rigby, H. E. (2009). Effect of plyometric training on swimming block start performance in adolescents. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(7), 2137-2143.

Milewski, M. D., Skaggs, D. L., Bishop, G. A., Pace, J. L., Ibrahim, D. A., Wren, T. A., & Barzdukas, A. (2014). Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 34(2), 129-133.

Morin, J. B., Slawinski, J., Dorel, S., Couturier, A., Samozino, P., Brughelli, M., & Rabita, G. (2015). Acceleration capability in elite sprinters and ground impulse: Push more, brake less?. Journal of biomechanics, 48(12), 3149-3154.

Blazevich AJ, Gill ND, Bronks R, Newton RU (2003) Training specific muscle architecture adaptation after 5-wk training in athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 35:2013–2022

Turner, A. M., Owings, M., & Schwane, J. A. (2003). Improvement in running economy after 6 weeks of plyometric training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 17(1), 60-67.

About The Author

Todd Davidson is a UKSCA accredited Strength and Conditioning Coach currently undertaking a PGCE through St Mary’s University, with the longer term aim of introducing athletic development into the national P.E curriculum. Todd\’s current interest on youth athletes was sparked by gaining experience with University, Paralympic and Olympic athletes as part of his internship roles with Durham University, Middlesex County Cricket Club and the English Institute for Sport, with GB Boxing and Paralympic Table Tennis, and speaking to other practitioners as to how this journey can be scaled more effectively to reduce injury risk, enhance performance and improve athletic development in youth athletes.

Todd can be found via:

Twitter: @todddavidson93

Facebook: search Todd Davidson P2P coaching

Instagram: @ToddDavidsonP2Pcoaching

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1570447612337_73339 {

}