Trunk Training for the Youth Athlete

Part 1 (Read here) of this series discussed the anatomy of the different muscles of the trunk and how this determines function as well as how you can categorise your trunk training to maximise your athletic performance

Part 2 (Read here), introduced the concept of low load stability and why it can serve as a great foundation for more advanced trunk work to follow.

Part 3 (Read here), focused on high load stability trunk training.

Today we bring you the fourth and final blog post in the Trunk Training for the Youth Athlete series.

How do we fit this together?

With the various trunk training adaptations, it’s easy to be fooled into thinking you have to dedicate an entire training session just to trunk exercises.

The reason why this is not the case is that oftentimes these adaptations are covered elsewhere in a decent strength and conditioning program.

For example:

-

athletes who are competently performing squats and deadlifts will be developing high load stability/trunk strength simply by having to maintain their posture under load

-

athletes who perform multi-planar plyometric or jumping and landing in different directions are having to stabilise in the frontal and transverse planes

-

athletes who perform unilateral or asymmetrical step-ups and farmers walks will already be having to stabilise themselves in the frontal plane to prevent excessive sideways bending and their knees caving in

#block-901c392203936f20ac50 {

}

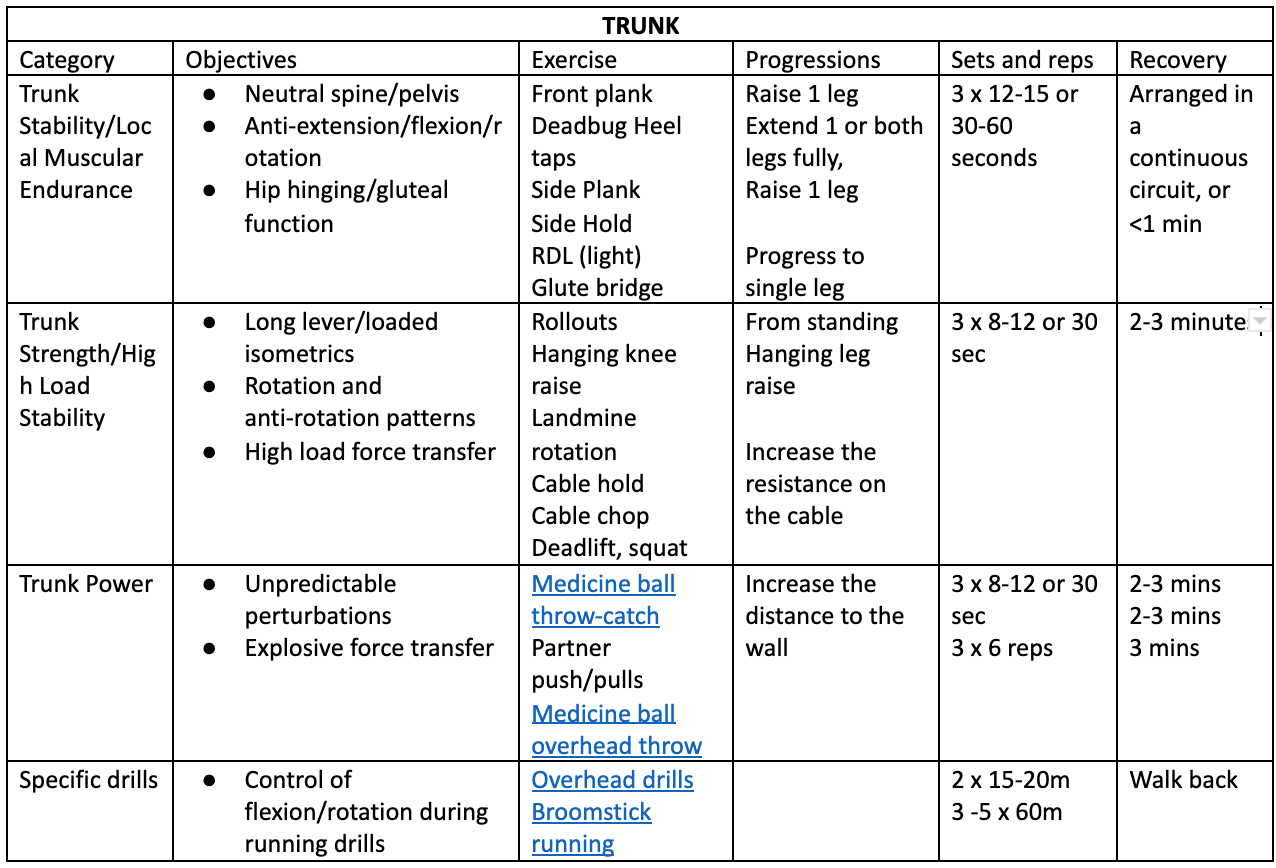

Whilst it would be impossible to list every regression or progression, the above summary table brings together the information that has been presented through parts 1-3 of this trunk training series.

Although it is not a bad template to follow, it is overly simplistic to train a block of trunk stability, then trunk strength, and conclude with trunk power. Youth athletes can also lose previously developed trunk stability when they enter growth spurts, which may also see previously nailed on technique, such as basic squatting and hip bending patterns, thrown out the window.

Closing Thoughts

The ability to create movement (e.g. possessing the range of motion) and resist it can and should be trained alongside it. There is no good having an athlete who can plank for days but has no capability to rotate.

We need to ensure that our athletes have the mobility to create motion, the stability and stiffness to reduce unwanted motion at low and high speeds, and the coordination of power the transfer force from the lower to upper extremities.

Since the trunk is involved in pretty much every sporting activity it can be helpful to develop a trunk that can produce force on demand, in more specific movement patterns.

Ultimately sports performance is the name of the game and this is where we want to see our trunk training manifest itself. As ever though, context is king, just because an exercise looks more ‘specific’ does not necessarily mean it’s the best choice for that athlete at that time.

Any gains in ‘sport-specific’ trunk training, need to be built upon a general foundation of creating and resisting movement. That said, below are just a few examples that can complement a holistic trunk training program

Practical Recommendations

-

Include exercises that challenge your athlete’s ability to resist and create an extension, flexion, rotation and lateral flexion

-

Pair an exercise where the athlete resists a given movement with one where they create it (For example, anti-rotation presses with medicine ball rotation throws)

-

Including loaded carry variations (single arm overhead variations can be used to challenge low load stability, whereas farmers walks can challenge high load trunk stability)…choose accordingly

-

Grouping low load stability exercises together can challenge the trunk musculature from an endurance perspective whilst highlighting weak links in the chain

-

‘Sport-specific’ trunk work and medicine ball throws can be used to improve the use of the trunk musculature in explosive actions

References

Aspe RR, Swinton PA. Electromyographic and kinetic comparison of the back squat and overhead squat. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2014;28(10):2827– 2836. PubMed doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000462

Fletcher, I. (2014). Myths and reality: training the torso. Professional strength and conditioning, 33, 25-29.

Mcgill, S. 2007. Low back disorders: Evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation, second edition. Champagin: Human Kinetics

Spencer, S., Wolf, A. and Rushton, A., 2016. Spinal-Exercise Prescription in Sport: Classifying Physical Training and Rehabilitation by Intention and Outcome. Journal of athletic training, 51(8), pp.613-628

Recommended Resources

Below are links to the books and journal articles on which this 4 part series has been based:

High Performance Training for Sports, Chapter 4, Stabilising and Strengthening the Core

National Academy of Sports Medicine, Chapter 9, Core Training Concepts

An Introduction To Medicine Ball Training by Eamonn Flanagan

About The Author

Todd Davidson is a UKSCA accredited Strength and Conditioning Coach currently working at Downe House school, in charge of the scholarship athletes\’ strength and conditioning program whilst introducing athletic development into the P.E curriculum.Todd\’s current interest on youth athletes was sparked by gaining experience with University, Paralympic and Olympic athletes as part of his internship roles with Duham University, Middlesex County Cricket Club and the English Institute for Sport, with GB Boxing and Paralympic Table Tennis, and speaking to other practitioners as to how this journey can be scaled more effectively to reduce injury risk, enhance performance and improve athletic development in youth athletes.

Todd can be found via:

Twitter: @todddavidson93

Facebook: search Todd Davidson P2P coaching

Instagram: @ToddDavidsonP2Pcoaching

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1566481055186_19750 {

}